we're not talking about death enough

pragmatism, book recommendations, and why I shouldn't plan your funeral.

Warning: This piece has discussions of death, dying, and human remains. I’m talking about decomp again. Sorry. Please stick around.

Last weekend I found myself sitting at a 7 year-old’s tea party talking about open air cremation sites. The Crestone End of Life Project, to be precise.

Crestone is a legal, open-air pyre in Colorado, and I find the bioethics of open-air cremation fascinating. How do you manage the smoke dispersal? How do you navigate the biohazards? How do you preserve the sanctity of human remains?

Halfway through, I realized that this may have been an inappropriate topic for a tea party.

Luckily, the 7 year-old’s mother was just as fascinated by open-air cremation as I am, and I was not forcibly ejected from the house and put on a list. But for a moment, I forgot that children are typically shielded from death. They’re either brought to it slowly, or told well-meaning lies that leave them unprepared and naive.

I never had that. I don’t know when I learned about death, but it felt like something I always understood, something I didn’t need to be shielded from.

Death is part of life. Everyone and everything has a time to die. To me, the choice was always not if we talk about it, but how.

why children need either necromancers or catholicism

if you don’t have any dogmatic cannibalism at home, cold case files will do

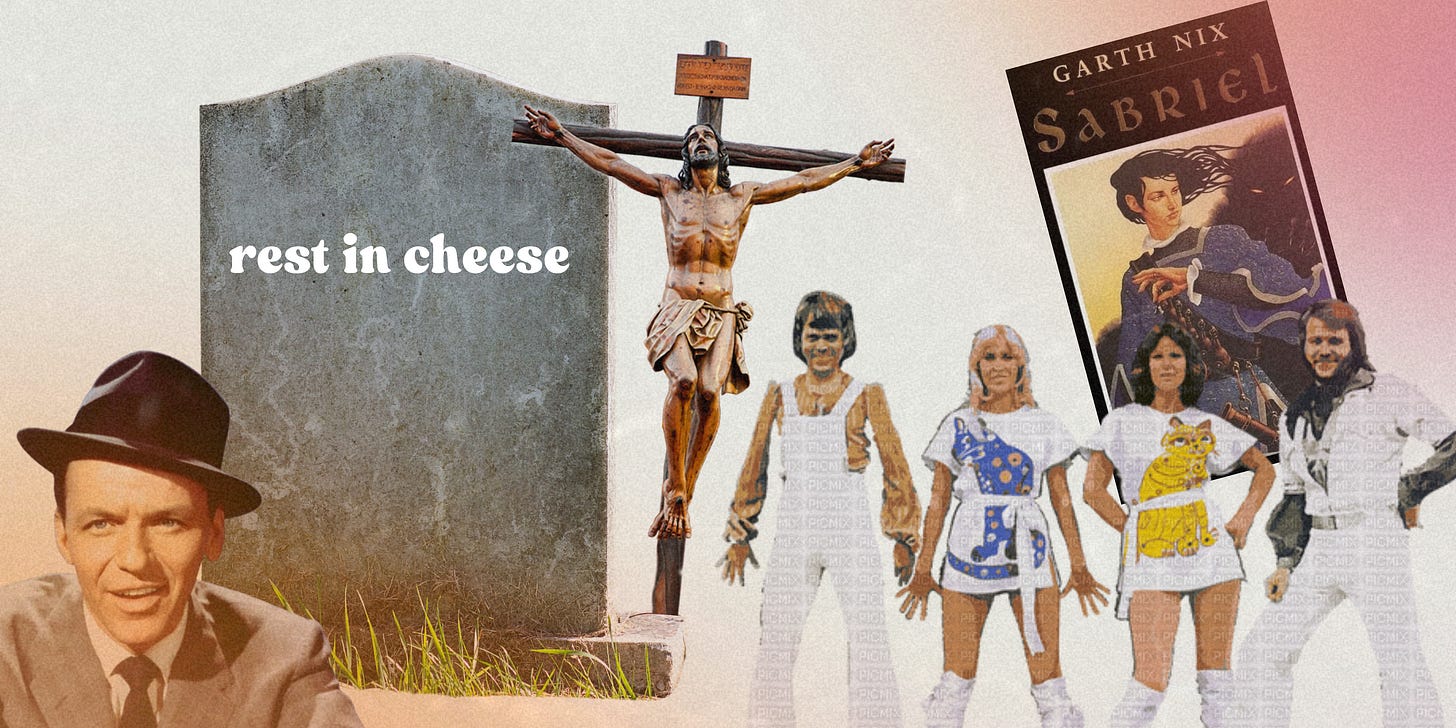

In my most vivid childhood memory, I am about seven or eight, sitting on the top balcony of my childhood home, drinking a Coke and reading about necromancy.

The sun is warm and not oppressive, so it must be spring. Through the screen-glass door, the TV is on. This is pre-9/11, which means my family hasn’t become a slave to the 24/hour news cycle yet. Based on the sun, it’s morning, which means the TV is likely playing Law and Order to an empty room.

The book I’m reading is Sabriel by Garth Nix. It’s the story of a young necromancer who, armed with bells and a cat, is responsible for restoring the balance of life and death. She walks through Death, which takes the form of a river and nine gates. In the chapter I am reading, she had just found her missing father, locked away behind one of Death’s waterfalls. She will use her bells to give him a chance to walk in life once more, but it will be only temporary. This is one of the themes of the book: Everyone and everything has a time to die.1

At this age I have not yet been to a funeral. I haven’t watched tiny, TV-pixelated people jump from the Twin Towers. I have lost pets, though. I’ve held a bird as it died in my hands, its guts pulled out by a local carnivore. I’ve examined jaw bones that my grandpa dug up in his yard, and I’ve run my fingers over the feathers of mounted birds, finding the little divots were the buckshot broke the skin. I’ve used shaving cream to restore old headstones and played hide-and-seek in the overgrown grass of the family cemetery.

I go to church and consume the body of a dead man, drink his blood and run my fingers over the image of his desecrated, dying body. I am told I am dust, and to dust I shall return. I fall asleep most nights laying beside my mother as we watch Cold Case Files, my sleeping mind consuming words like decomposition and human remains. And I am reading books that teach me about the cycle of life, the inevitability of death, and the importance of respecting that balance.

I am taught that bodies are bodies and souls are souls, and death is everywhere.

When I do attend my first funeral, the sun is beating down and everyone is wearing black. My father is not handling this death well. He is always uncomfortable with funerals, spooked by death. They make him feel itchy and ill-fitting in his skin, and the presence of the body grates against his back molars. If he fusses with his tie enough, or curses at his ringing phone, maybe he can pretend that death does not exist.

Years later, this will become a family story. Remember when Dad got so freaked out during Irene’s funeral that he threw his ringing phone in the bushes instead of answering it?

I was fine at that funeral, because I felt like I knew a secret my dad had yet to understand. Irene was not there. She was in the river, past the gates. What we were burying was just her body. An organic leftover. A jawbone in the dirt, skin cells catching the sunlight, a cat whisker stuck in a blanket.

Why be scared of that?

why adults need books about decomposition

Around the start of the pandemic, I began reading about death: the biologic processes of it, the financial and ecological burdens associated with the funeral industry, and the varied ways that cultures honor their deceased loved ones. My mother wasn’t dead or dying at that point—that came three years later. My search was academic, not philosophical.

If you are inquisitive and don’t mind some gross descriptors, I really do recommend the following nonfiction books:

From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death by Caitlin Doughty

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

All That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving Crimes by Sue Black

Smoke Gets In Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory by Caitlin Doughty

Death's Acre: Inside the Body Farm Forensic Lab Where the Dead Do Tell Tales by Jon Jefferson and Bill Bass

Preserved: A Cultural History of the Funeral Home in America by Dean G. Lampros

The American Way of Death Revisited by Jessica Mitford

These books manage to be funny, dark, thought-provoking, and deeply touching. I listened to them while folding laundry and walking the dog, read them next to the pool and on vacation with friends. It may seem like death as entertainment, but these books aren’t sensationalizing death: they’re humanizing it. And through them, I saw my childhood secrets laid clear for all the world. I was not callous, or morbid, or strange. I was death positive.

what is death positivity?

Founded by Caitlin Doughty, the death positivity movement2 is not about being stoked that my mom died. It’s about having open and honest discussions about death, engaging with grief, and adjusting the framework in which we honor our dead.

The movement has eight core tenets:

That by hiding death and dying behind closed doors we do more harm than good to our society.

That the culture of silence around death should be broken through discussion, gatherings, art, innovation, and scholarship.

That talking about and engaging with my inevitable death is not morbid, but displays a natural curiosity about the human condition.

That the dead body is not dangerous, and that everyone should be empowered (should they wish to be) to be involved in care for their own dead.

That the laws that govern death, dying and end-of-life care should ensure that a person’s wishes are honored, regardless of sexual, gender, racial or religious identity.

That my death should be handled in a way that does not do great harm to the environment.

That my family and friends should know my end-of-life wishes, and that I should have the necessary paperwork to back-up those wishes.

That my open, honest advocacy around death can make a difference, and can change culture.

Reading more about the culture and science of death, and engaging with the content produced by the death positivity movement, has made me incredibly curious as to why people—especially those in Western cultures—are so strange about bodies. Why are we so terrified of flesh and decomposition that we pump our remains full of embalming chemicals to stave off the process, even when we’re out of sight under dirt and steel and concrete?

Our modern notions of death and dying are neither normal nor traditional. They are born of capitalism and oppression, the result of a system that has convinced us our flesh is taboo and unclean, that the only true dignity of death is for it to be as convenient and sanitized as possible. In pursuit of this false dignity, we have created a culture of silence and discomfort around death and mourning. And we pay handsomely to maintain it.

why i’m okay with death, even though it fucking sucks

we’re going to get sad about my mom for a moment, but the next section is funny, don’t worry

What I have learned through reading, living—and yes, even Catholicism—is that there is something lovely about the body, its decomposition, and the life it can live next. I find solace in the idea of my mother’s ashes floating somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean, or sunk to become sediment. I find value in my organs being donated when I’m gone, to let a little piece of me live on in another. There is beauty in the body farm, in the miraculous ways that a human form can continue to change after death, to create new life.

I know that not all deaths are beautiful. My mother’s death was not. Her friends’ deaths were not. Many people do not have the privilege to die in comfort, to slip away in their sleep, or even to have their remains treated with dignity. Many, many deaths are horrifically unfair.

Being death positive doesn’t whitewash trauma into a holy thing. It hasn’t taught me how to master grief. Every day I find myself wishing my mother wasn’t dead. That she hadn’t been so young. That it hadn’t been so sudden. That it hadn’t been so slow.

But these feelings are part of life as well. Grief comes on just like sunny days, and sometimes all you can do is sit and drink it in. Like our flesh, the grief will break down over time, will turn sour and bloated and ugly before softening into something fertile and new.

My mother was able to pass at home, surrounded by her family and animals. Despite how mind-numbingly terrible it was to lose her, I believe that she had as good a death as we could give her. And I have to take solace in that.

why you don’t want me to freestyle your funeral

In the last few years, I have entered that stage of adulthood where the people I still think of as actual adults are beginning to die, and decisions have to be made. Some of my loved ones left very clear instructions for their services, like reenactors and bagpipers. Most didn’t.

For example, we were given a portion of my grandmother’s ashes, to handle as we saw fit. We are not an urn on the shelf family, and because my grandma never talked about her funeral wishes, my husband and I awkwardly dispersed her ashes at a local battlefield while playing Love and Marriage. I chose the location because it was close to her house, and I thought she’d like how peaceful the woods were. I chose the song because she once made me listen to it on repeat for a whole summer while she drove 40 miles over the speed limit. Also, she had the hots for Frank Sinatra.

I do not think this is what my grandmother would have chosen, but because it was left up to the worst of her grandchildren, that is what she got.

And so, because I know you all do not want to be scattered at a Civil War battlefield accompanied by a song you once got into a fender-bender while listening to, I have begun a relentless campaign to force people to talk to me about death.

No, don’t run away, let’s just chat.

So what do you want? What feels right? Do you want to be cremated and spread? Do you want to be planted into a tree? Do you want a gravestone your family can visit? Do you want to be sent to space, or buried in an eco-coffin, or donated to science?

My father wants to be put in a wood chipper. I will ignore this, because it is a crime, and cremate him. My best friend’s mother wants to be buried in a Roman Catholic natural cemetery run by Cistercian Monks. I want to be composted, turned into dirt and added to a forest that is being rebuilt. My husband does not want a funeral. I want a party where the queso never stops flowing and everyone who loved me is forced to listen to ABBA’s Greatest Hits album.

I am trying to do for my loved ones what Sabriel and Caitlin Doughty and the fucked-up spookiness of Catholicism did for me, to help prepare them for life’s great inevitability, to create comfort around the cycle of death. I am talking about cremation at tea parties.

Being pragmatic about death doesn’t magically fix grief and anxiety. But it will make things less scary. We are dust and soil, and everyone and everything will die. Why not choose to find the beauty in it where we can?

If you’re a fan of audiobooks, Tim Curry narrates not only Sabriel, but the entire Abhorsen trilogy.

The death positive movement even has a 501(c)(3) organization associated with it, The Order of the Good Death. The Order not only endorses the tenets of the death positive movement, but takes it a step further in actively trying to amend the existing Western funeral industry, by which they “design practical resources, pursue new and amended legislation, and provide support for alternative forms of death care.”

I feel like I've always understood death as well. My grandad, who we lived with, died when I was five and multiple times when discussing it my parents have said that I was too young to understand, but that's never felt true to me.

Me and my middle brother were deemed too young to go to the wake and removal the day before the funeral, but were taken to see my grandad's body privately in the funeral home. I remember telling my mum that he felt cold, so maybe I didn't fully understand the mechanisms of his body no longer being alive, but I do feel I understood my grandfather was permanently gone (at least from this plane of existence). I guess at the end of the day it comes down to you definition of what it means to understand death...

yeah so i love you. i selfishly self consciously worry i talk about it too much. i feel like i was born into it and i've seen so much of it and i WANT to talk about it but it's like holding a ball of lava a lot of the time. thank you for this